What is porphyria?

Porphyria is pronounced similarly all over Europe, but the spelling varies considerably: porfiria, porfyrier, porfyria and porphiria.

- The porphyrias are a group of relatively rare genetic disorders.

- They are called the porphyrias because they cause a build up of chemicals called porphyrins (the purple-red pigments named from the Greek for purple), or the simpler chemicals used by the body to make porphyrins.

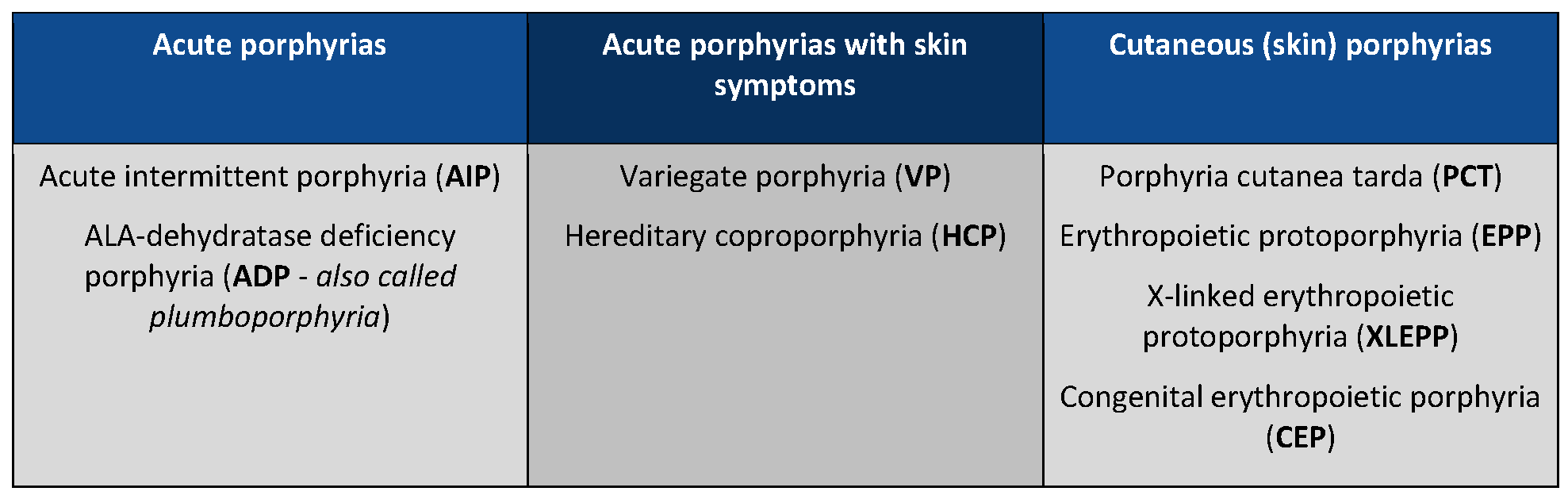

- The porphyrias are broadly categorised into acute and cutaneous (skin), according to the symptoms suffered. Some acute porphyrias also suffer from skin symptoms (VP and HCP).

- The severity of symptoms varies dramatically in all types of porphyria. But no matter which type, the more knowledgeable about their condition a patient is, the more they are likely to stay well.

Further details can be found on the porphyrias pages, but briefly, the main types are:

Read more about the science...

- Most of the porphyrias are inherited and result from a faulty gene, which leads to difficulty making a chemical called haem – a constituent of many important proteins in the body. Haem is also a component of haemoglobin, which has the vital function of enabling the body’s cells to use oxygen.

- To produce haem, the body needs to convert porphyrin precursor chemicals ALA and PBG (aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen) into more complicated substances called porphyrins. These are then converted from one type of porphyrin into another to form haem. The steps in this process, or ‘pathway’, are carried out by a number of proteins known as enzymes. If a fault develops in an enzyme or a fault is inherited due to a gene mutation, the process may not work properly and this can cause haem precursor chemicals to accumulate, which can cause severe medical problems.

- The type of porphyria varies according to the enzyme that is affected.

- When porphyrins accumulate in the skin, it becomes very sensitive to sunlight and this causes the skin symptoms of porphyria (cutaneous porphyrias). Accumulation of the simpler chemicals in the liver leads to acute attacks of porphyria.

Acute porphyrias

The acute porphyrias (AIP, ADP, VP and HCP) are grouped together because acute attacks of porphyria occur in each one. These attacks are uncommon and are often difficult to diagnose. About 1 in 75,000 people suffer from them.

Acute attacks are caused by a build-up of ALA and PBG (aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen) which result in damage to nerves. ALA and PBG are the raw materials for making haem.

Typical features of acute attacks:

- Severe pain in the abdomen, back, arms or legs

- Nausea, vomiting and constipation

- Low sodium (salt) levels in the blood

- Pulse rate and blood pressure may increase

- Confusion

- Convulsions and muscular weakness

Acute porphyria attacks are often triggered by exposure to commonly prescribed drugs, illegal drugs, alcohol, dieting, stress, infections, viruses and hormonal fluctuations.

In addition to acute symptoms, VP and HCP can cause blistering of the skin in sunlight – the skin can become fragile and should be protected. In HCP skin problems tend to occur during an attack, whereas in VP, the skin changes and acute attacks may occur at different times.

Cutaneous (skin) porphyrias

The skin porphyrias (PCT, EPP, XLEPP and CEP) cause sensitivity to sunlight on exposed areas of skin. Sunlight should be avoided as much as possible (please see our Skin safety page for more advice). As with all porphyrias, the severity of the problem varies. People with skin porphyrias do NOT need to stick to the SAFE drugs list used by those with acute porphyrias.

PCT is the most common of the skin porphyrias, and is the only porphyria which is not always inherited. It can be triggered later in life by heavy drinking, iron tablets, oestrogens, certain drugs or by liver infections. In 20% of UK patients, it is caused by hereditary haemochromatosis. PCT is treated by phlebotomy (removing blood) or low-dose oral chloroquine, and sufferers need to avoid whatever triggered the problem.

EPP is a less common form of porphyria. Like the acute porphyrias, it is an inherited disorder. There are a variety of genetically different forms of EPP – the autosomal recessive form makes up 97% of cases, and there is also the X-linked form: XLEPP.

Sunlight does not always need to be direct – light reflected off water, sand or snow, or passing through window glass may also cause symptoms. EPP is different from the other cutaneous porphyrias as it doesn’t cause blistering. In bright light, the skin becomes very painful but there is usually little to see.

There is no easy treatment. It is mostly a matter of avoiding bright light.

CEP is a very rare disorder. It is a multi-organ disease predominantly affecting skin, eyes and bone marrow and can cause severe scarring due to sensitivity to visible light. Severe cases may need bone marrow transplants.

Read more about each of the conditions on the porphyrias pages.