Testing and diagnosis

An accurate diagnosis of porphyria is vital in order that patients and their families can learn the best ways to deal with their condition. Despite this importance, testing causes confusion among patients and medical professionals alike. Fortunately, once a doctor has thought to investigate porphyria, it is relatively easy to eliminate or confirm a diagnosis.

If diagnosed, it is advisable to see a porphyria specialist for advice on how to live with the porphyria. For most porphyrias, there are various possible treatments.

In each type of porphyria, there is a distinctive pattern of porphyrins in blood, urine and faeces. This is very useful for diagnosis. However, levels of some porphyrins may be normal in people with porphyria who do not have current symptoms. Also porphyrin levels may be raised in people with other medical conditions who do not have porphyria.

For these reasons, diagnostic testing is best done by a specialist porphyria laboratory. As they can interpret the exact patterns of each porphyria to determine an accurate result.

Since porphyrins are affected by light and degrade easily, test sample containers should be wrapped quickly after taking. You can use either foil or black plastic.

The information on this page is taken from our testing and inheritance leaflet.

Further guidance for your and your doctor

More detail on testing and diagnosis can be found at:

- Kings College Hospital, London: www.viapath.co.uk/our-tests/porphyria-service-saas

- University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff: www.cardiffandvaleuhb.wales.nhs.uk/porphyria-service-cardiff

- Epnet: https://porphyria.eu

Diagnosis of an ACUTE porphyria

If suffering from symptoms that could potentially be caused by acute porphyria, the first test that should be done is a urine porphobilinogen (PBG) test, and in some cases urinary ALA too. In some acute porphyrias the levels of PBG can drop quite quickly after the attack subsides (within about a week). Therefore the test needs to be done during the attack to be reliable. If the PBG level is raised, this will be followed by further biochemical testing to confirm which porphyria is present.

If there is a family history of acute porphyria, a referral to a porphyria specialist will be needed for screening. There are two possible methods:

- Biochemical testing

- Genetic testing: however, this is only possible if a definitely affected family member has already had genetic testing.

Diagnosis of a CUTANEOUS porphyria

If suffering from symptoms of photosensitivity, a skin porphyria may be suspected. This can be confirmed by biochemical testing.

Family screening may be done depending on which skin porphyria is at play.

Diagnosis of an acute attack

Once it is known that someone has an acute porphyria, a PBG test can be used to check whether symptoms (e.g. pain) are due to an attack. If it is not an attack, other possible causes can be looked for (e.g. abdominal pain could be appendicitis). It is important that people with porphyria do not assume that all their illnesses are porphyria, as common but potentially serious conditions could be overlooked.

What is biochemical testing?

Biochemical testing involves checking the porphyrin and porphyrin precursor levels in urine, blood and faeces. This method is used to diagnose all types of porphyria as each have a distinctive pattern of raised levels.

What is genetic testing?

Genetic or DNA testing is done on a blood or saliva sample. It is not feasible to use this method alone for diagnosis, since there are too many genes and possible faults. Biochemical testing is used together with an assessment of symptoms. Once a porphyria is known, a genetic test can often find the fault in the gene.

If the fault is found, other members of the family can then be checked relatively quickly. New babies of gene carriers can be tested in the months after birth very easily with swabs taken from the mouth. Please speak to your porphyria specialist if you would like to do this.

How do we inherit porphyria?

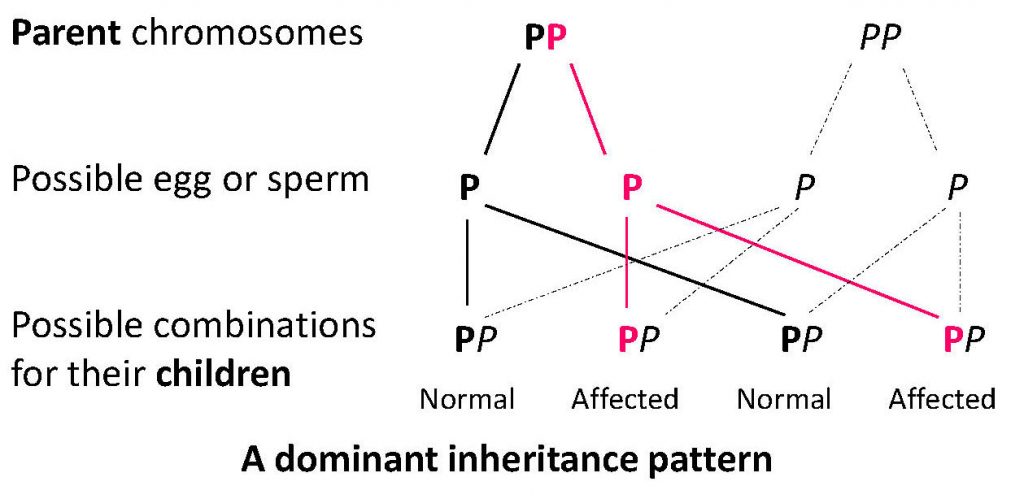

Human body cells each contain 23 pairs of chromosomes. These chromosomes carry our genes. We get one set of chromosomes from each of our parents, one set from the mother, the other from the father. Which chromosome we get from each pair is completely random, but will determine whether or not a porphyria is passed on to a child.

Porphyria genes can be dominant or recessive depending on the type of porphyria. The inheritance pattern for a dominant gene is shown here: P is the porphyria gene, P is the normal gene.

AIP, VP, HCP and familial PCT all occur due to dominant genes. If you have one of these porphyria genes (P in the diagram), you could be ill or have skin symptoms. There is a 50% chance of inheriting one of these porphyrias if one of your parents has porphyria.

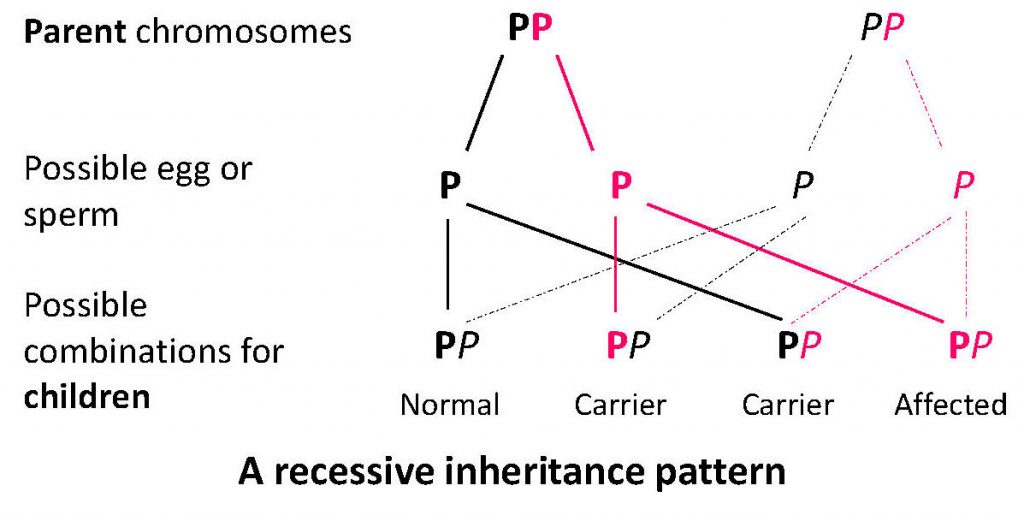

CEP, ADP and HEP (a rare form of PCT) occur due to recessive genes. One P gene doesn’t cause problems, as the second gene works properly. So, those with one P gene in the diagram wouldn’t have porphyria. Two porphyria genes, PP (one from each parent) will cause problems.

CEP, ADP and HEP (a rare form of PCT) occur due to recessive genes. One P gene doesn’t cause problems, as the second gene works properly. So, those with one P gene in the diagram wouldn’t have porphyria. Two porphyria genes, PP (one from each parent) will cause problems.

EPP is also recessive, but there are two P genes. One is common (Pc), and causes no real problems, even when someone has two copies (PcPc). The second gene is rarer (Pr), and has a much more severe effect. Usually, people with EPP have one of each (PcPr) and the combination is severe. In many cases parents are unaffected, since each have only one type (Pc or Pr). However, the pattern of inheritance can be different in some families, in particular for those with XLEPP.

EPP is also recessive, but there are two P genes. One is common (Pc), and causes no real problems, even when someone has two copies (PcPc). The second gene is rarer (Pr), and has a much more severe effect. Usually, people with EPP have one of each (PcPr) and the combination is severe. In many cases parents are unaffected, since each have only one type (Pc or Pr). However, the pattern of inheritance can be different in some families, in particular for those with XLEPP.

What are the consequences for families?

AIP, VP and HCP: Although there is a 50% chance of inheriting a P gene, only about 1 in 5 people affected will be ill, so many people have no idea that they have it. We don’t yet know the reasons for this, but we do know about things that can trigger attacks (such as alcohol and drugs). Please see our acute porphyria pages for more information on symptoms and treating these conditions.

Blood relatives do need to be tested (preferably via genetic testing) to check whether they have an acute porphyria, so that they can avoid the triggers. (Women are particularly at risk as hormonal changes can cause attacks.)

Familial PCT is also dominant (50% chance of inheritance) with the gene affecting about 1 in 5 of those who have the affected gene. However, many experts think genetic testing for relatives is not useful as PCT needs an environmental risk factor to trigger skin problems, and it is treatable.

CEP, HEP and ADP are recessive forms of porphyria. Because a single P gene doesn’t cause problems, the parents are usually unaffected. Similarly, the children of those affected are usually unaffected. However, the effects of these genes can be nasty. With CEP in particular it is advisable to talk to a genetic counsellor.

EPP: Because of the way EPP is usually inherited, it is advisable to test the partner of someone with EPP for the Pc gene. It is then possible to predict whether their children could have EPP.